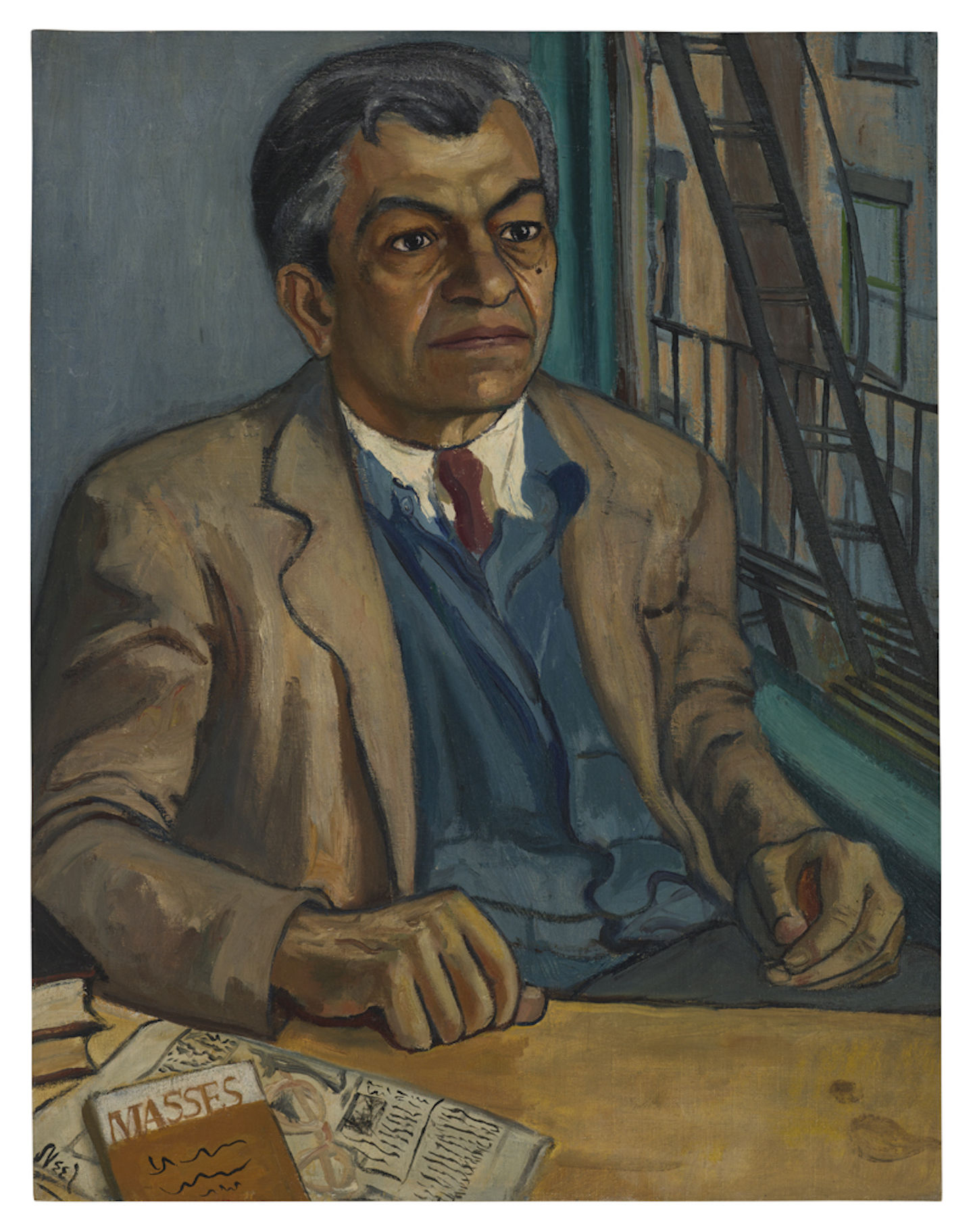

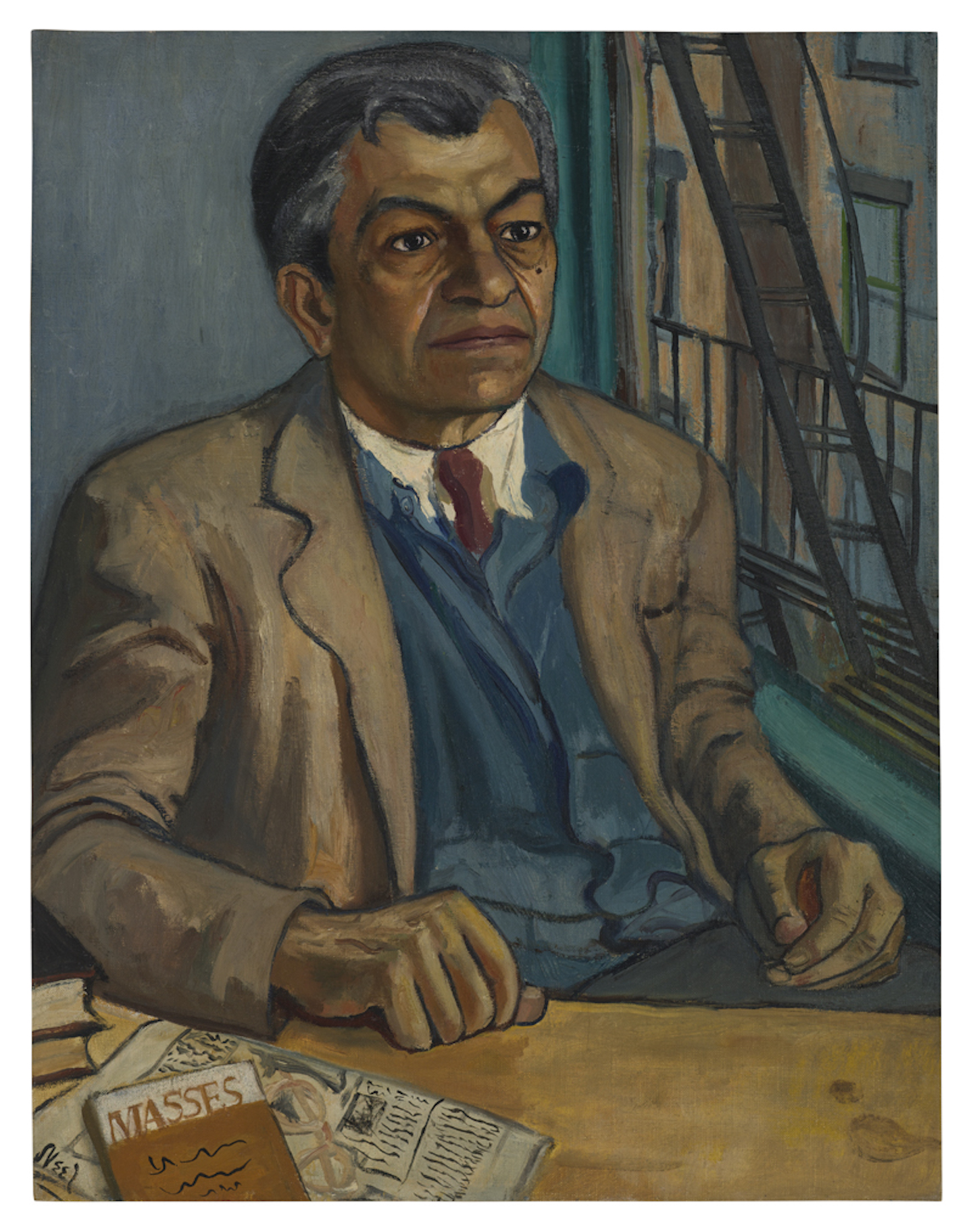

Alice Neel, Mike Gold, 1952. © The Estate of Alice Neel Courtesy (Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner)

Is it time to release Michael Gold from his personal gulag to range free in the pastures of 20th-century American literature?

Gold—“Mike” to his comrades—was a key figure in American letters from the mid-1920s well into the Great Depression. A leading advocate and practitioner of “proletarian literature,” he was also the editor of New Masses, perhaps the most important left-wing periodical of the 1930s. A committed, vociferous revolutionary, he joined the Communist Party in the 1920s and then stuck with it for life. Neither purges nor pacts nor the 1956 invasion of Hungary would cause Gold to renounce his faith. On the contrary. A columnist for the Daily Worker for a quarter century or more, Gold also served as the party’s preeminent cultural commentator—albeit less the voice of the leadership than of the rank and file. But what goes around comes around. Railing for decades against perceived “literary renegades,” he was, arguably, both an early adapter and a victim of cancel culture.

In his new biography, Michael Gold: The People’s Writer, Patrick Chura calls Gold “the best American writer that is still largely unknown to Americans” and makes it clear why he thinks Gold should finally be released from his political prison. True, Gold’s 1930 autobiographical novel, Jews Without Money, was republished in the mid-1960s and is now recognized as a landmark of Jewish American literature. But Chura argues that Gold’s journalism, plays, poems, and criticism deserve our attention as well. After all, the Gold that emerges from his book was not just a 1920s rebel and a 1930s radical but also a forerunner—more in his aesthetics than his politics—of the Beat 1950s and countercultural 1960s.

Born in 1893, the eldest son of impoverished Yiddish-speaking immigrants from Hungary and Romania, Itzhok Granich was raised in the squalid depths of the Jewish Lower East Side. At 12, he was forced to quit school to support his indigent family with menial jobs even as he nursed literary ambitions, publishing poems that denounced poverty in a settlement house newspaper.

By 20, Granich managed a few semesters of night school, studying journalism at New York University. A year later, he was submitting revolutionary verse to Floyd Dell and Max Eastman, editors of The Masses, an illustrated journal devoted to radical politics and bohemian culture, a forerunner of the underground press. Then, in a burst of heroic chutzpah, the young man, now Irwin Granich, managed to talk his way into Harvard as a “special student,” supporting himself with an anonymously written daily column in the Boston Journal, “A Freshman at Harvard,” for which he received $15 per week (the equivalent of $400 today).

The column was a blog avant la lettre; its attitude is strikingly contemporary. Whatever his editors might have wanted, Granich privileged his socialism over his social life and emphasized class consciousness above all. A Jew without money questioning Harvard’s social ideals, as well as his professors’ authority, proved more than the university or the newspaper could stomach. Among other things, Granich compared Harvard to Cooper Union, then the tuition-free jewel of the Lower East Side, praising the latter as a school “where knowledge and not marks are the real end sought.” (Having taught at both institutions, I can attest to the prescience of this critique.)

Granich’s foredoomed attempt to storm the Ivy League recalls the hero of Martin Eden, Jack London’s autobiographical novel about a self-made proletarian writer. The strain of studying and writing under deadline while living on a subsistence diet precipitated a nervous breakdown—both for Eden and for Granich. Remaining in Boston for a year, sometimes living on the street, other times crashing with an anarchist commune, Granich returned to New York in 1916. There, he embarked on an upward trajectory that zigzagged through radical politics and bohemian art. He also took on a new name: Michael Gold.

Writing for the socialist New York Call, Gold interviewed Leon Trotsky during his sojourn in the Bronx, reported on John Reed’s return from Russia, and took Theodore Dreiser on a tour of the Lower East Side. Having dodged the draft by living in Mexico, he began working on the book that became Jews Without Money. He also wrote one-act dramas for the Provincetown Players. One, titled Money, appeared on a bill with plays by Edna Ferber and Djuna Barnes.

Gold hung out with Eugene O’Neill, who advised him to lay off the propaganda, and became romantically involved with the Catholic radical Dorothy Day. (They were even briefly engaged.) Meanwhile, his journalism career took off. At one point, he shared editorship of The Liberator, Eastman’s successor to The Masses, with the West Indian poet Claude McKay, one of the leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance.

This short-lived partnership would be excoriated by Gold’s one-time Worker colleague Harold Cruse as an example of Gold’s bad faith in his relations with Black comrades as well as his bullheaded belief in the Soviet school of workers’ writing called Proletkult. Chura, who seldom finds fault with Gold, cites more recent research to suggest that the quarrel was more a matter of individual temperament than opposed ideology. Strong-willed, self-made outsiders, both Gold and McKay considered themselves proletarian writers and saw racism as a threat to the workers’ movement. But McKay was also the more refined stylist, and their differences may have had to do as well with Gold’s tolerance for rough-hewn worker prose.

Chura twins these two together: Gold’s artistic preferences and his political radicalism. The Gold of the 1920s drew inspiration from Carl Sandburg and Ernest Hemingway, both with roots in journalism, but he was also impressed by the Soviet avant-gardists Vsevolod Meyerhold and Vladimir Mayakovsky, not least for their fusion of artistic and political revolutionary esprit. In a paean to America’s Steel City, written after reporting on the 1922 United Mine Workers strike, Gold declared that “it was Pittsburgh that created Carl Sandburg and Eugene O’Neill, Dada, Futurism, Bolshevism, Capitalism, Gary and Lenin. Pittsburg is the material and spiritual capital of the twentieth century world.”

A futurist bard, Gold published short pieces—often reworked reportage—and “proletarian chants” in the Daily Worker and The Liberator. Some, a crude bridge from Walt Whitman to Allen Ginsberg, compared America to a runaway freight train. Others despaired of Americans who worshipped a “Money God,” their hearts hardened by Ford motor cars and their brains transformed into a “cheap Hollywood movie.”

The Liberator became New Masses in 1926. A member of a contentious executive board, Gold was temporarily ousted as an editor, then restored, and in 1928 became editor in chief. His first issue included John Dos Passos, Ezra Pound, Dorothy Day, and Louis Untermeyer as well as illustrations by Hugo Gellert, Louis Lozowick, and Otto Soglow. It was hailed by the Daily Worker, reviewed, Chura writes, as though it were “a novel, play, symphony, or other unified work of art.” Subsequent issues had contributions by Theodore Dreiser, Upton Sinclair, Art Young, Tina Modotti, Diego Rivera, William Carlos Williams, Langston Hughes, and V.I. Lenin, along with much of Jews Without Money.

As much as he was a professional journalist, Gold was also a professional proletarian. Joseph Freeman, a fellow editor at New Masses whose background was similar, recalled that Gold “affected dirty shirts, a big, black uncleaned Stetson with the brim of a sombrero; smoked stinking, twisted, Italian three-cent cigars, and spat frequently and vigorously on the floor.” He was also a rising literary star who went fishing with Ernest Hemingway in Key West, was courted by Edmund Wilson (who commissioned his celebrated takedown of Thornton Wilder, “Prophet of the Genteel Christ,” in The New Republic), and was name-checked by Sinclair Lewis in his 1930 Nobel Prize speech.

“Mike Gold already has a place in American literature,” V.F. Calverton wrote in The Nation in 1929, comparing him favorably to London and Sinclair, two other “crude” writers. Indeed, Gold appeared as a character in Boston, Sinclair’s “documentary novel” of the Sacco and Vanzetti trial, and with the publication of Jews Without Money, was even hailed as the new Sinclair.

Gold was not the first Jewish American novelist. Nor was he the first to write about the Lower East Side. Abraham Cahan’s The Rise of David Levinsky appeared in 1917. Anzia Yezierska’s books were so popular she was given a Hollywood contract. But no previous Jewish American writer, perhaps no other American Jew save Emma Goldman (whose influence Gold acknowledged and then strategically erased) had been so assertive a champion.

Jews Without Money (the very title is a statement) assaulted readers with a Boschian vision of rampant filth, disease, hunger, and criminality in a world where prostitution is ubiquitous, gangsters rule, and children are dismembered by horse-drawn carts. “A curse on Columbus,” the father of child narrator Michael cries more than once. Capitalism is a system where “kindness is a form of suicide.”

Set at the dawn of the 20th century, when the Lower East Side was the most densely populated urban area on earth, but published only months into the Depression, Jews Without Money landed among the literati with the impact that slum memoirs like Claude Brown’s Manchild in the Promised Land and Piri Thomas’s Down These Mean Streets would have 35 years later. Gold opens by describing the “tenement canyon” where he lived as a boy: “It roared like a sea. It exploded like fireworks. People pushed and wrangled in the street. There were armies of howling pushcart peddlers. Women screamed, dogs barked and copulated. Babies cried.”

The Lower East Side echoed with the sounds of “a great carnival or catastrophe.” Not without a certain dark humor, Gold chronicles a succession of neighborhood crimes and tragedies, the exploits of the local youth gangs, people crushed and deformed by poverty, as well as a dreamy excursion to a vast park in the Bronx, more or less through the age of 12, when Michael is obliged to quit school.

Compressing the next decade into a couple of pages, the novel caps its account of blighted lives and inhuman conditions with its protagonist’s abrupt revolutionary conversion. After depicting his endless childhood season in hell, populated by false messiahs ranging from the savior foretold by a neighborhood Chasid to Buffalo Bill, Gold concludes Jews Without Money with the revelation the child had been seeking: “O Revolution that forced me to think, to struggle, and to live. O great Beginning.” O sudden Ending that would dog Gold for the rest of his career.

Published in February 1930, Gold’s provocatively titled novel was an instant sensation that went through 11 printings by October, the first anniversary of the stock market crash. (There were another 14 printings over the next 20 years as the book was translated into 16 languages.) Ironically, the Daily Worker’s review was notably hostile, complaining about the book’s $3 cover price, describing it as only “semi-proletarian,” and, worst of all, suggesting that “the suspicion of ‘pure artist’ creeps up on one out of Gold’s pages.”

The Worker was harsher still when it came to Gold’s quickly written follow-up, Charlie Chaplin’s Parade, a book for children published by an established firm and delightfully illustrated by New Masses (and New Yorker) cartoonist Otto Soglow. Identifying the presence of “master class propaganda,” the Worker warned Gold that “such stuff is impermissible for a supposedly proletariat writer” and wondered why, “at a period of sharpening class struggle, when the working class is striving to organize its forces for the battle,” the author chose to “spend time on a book like this?”

Did Gold take this to heart? In consigning his modernist fable to the bourgeois trash heap, the Worker’s critic bequeathed Gold with an attitude and an analysis that he would soon internalize, engaging in trench warfare against “supposedly proletariat writers” like John Dos Passos and James Farrell. But if they were sell-outs, so was he. In 1933, Gold opted for a regular paycheck by joining the Worker and earning a paltry $15 per column. Other writers, like his sometime colleague, the playwright John Howard Lawson, went to Hollywood. Gold had his own Dream Factory—the Communist Party.

Poverty was still a trap. Gold had little idea how to handle money. He hoped to take time to write another novel. Hemingway wrote in support of his application for a Guggenheim Fellowship; it was rejected. In a letter to Sinclair, Gold confessed his fear of penury: “I’m afraid that as usual I will have to forget fictioneering…may go back to the Daily Worker column, which pays a small wage but takes every bit of creative feeling out of me.”

By all accounts, Gold was an indifferent party member. He rarely attended unit meetings and in fact once wrote a column complaining about their tedium. Neither was he part of the leadership or a cultural commissar like Lawson or V.J. Jerome in Hollywood. Rather, he was a kind of blunt every-Red. He argued for sports coverage in the Worker and reversed his position on swing music when a flood of letters from Worker readers attacked his criticism of “hot jazz.”

Gold was also a loyal soldier. As a personification of the revolution, Stalin was infallible. The purge trials were a Western conspiracy. The Hitler-Stalin Pact stunned him into silence but, after a month, Gold resumed his column, defending the party line with such vehemence that he landed in the hospital. Then he turned on the onetime allies who, disgusted with the pact, had quit the CP-sponsored League of American Writers. These “literary renegades” included Hemingway, who left a personal message at the Worker office telling Gold “to go fuck himself.”

Still, the remaining rank and file loved him. The cover of Chura’s book is a 1939 photo of Gold, handsome and happy, seated among a group of fans after having given a lecture at what looks like a summer camp. The book’s first chapter describes a mass celebration honoring Gold and The Hollow Men, a collection of his attacks on Hemingway, Dos Passos, Sherwood Anderson, and others, as essentially a pep rally for the beleaguered party base.

Gold held his fire once Germany invaded the Soviet Union and the United States entered the war, but the Cold War stoked his ire toward perceived backsliders and comrade deviationists. In 1946, the same year he panned his old friend Eugene O’Neill’s new play The Iceman Cometh without, as he freely admitted, having seen it, Gold took the lead in excoriating the screenwriter-novelist Albert Maltz for daring to question party orthodoxy regarding the role of the artist. This, even more than Gold’s defense of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, was the last straw. There was no more worthwhile writing. Had there ever been?

While the essays collected in The Mike Gold Reader, a 1954 collection I found in a Cape Cod transfer-station swap shop, are generally uninspired, Chura cites work ranging from reportage to plays to poems to cultural criticism to punk polemics that might have changed my mind. These may not ensure Gold a passport into the Library of America, although the clamorous immediacy of Jews Without Money already belongs there, perhaps in a boxed set with Yezierska’s Bread Givers and former party member Henry Roth’s Call It Sleep—the cri de cœur of New York City’s immigrant Jewish ghettos.

Do any of the faithful ever get a pass? Many communists and devoted fellow travelers—from Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger to W.E.B. Du Bois (with whom Gold and his family used to celebrate Thanksgiving) and Paul Robeson—have largely been absolved by liberals. Some have even been commemorated on postage stamps. Jacob Lawrence’s engagement with communism is forgotten; the more sustained involvement of Alice Neel (hailed by Gold as an exponent of American socialist realism) is seen as a personal eccentricity. Yet as outspoken as Gold was, his scarlet letter “C” is indelible.

Gold was a zealot—a writer most at home writing paeans and jeremiads. He named one of his sons for Lenin, the other for Marx, and was an unrepentant Red until the day he died. In an often-hostile introduction to a 1996 edition of Jews Without Money, Alfred Kazin notes this zealotry and describes Gold as “a monumentally injured soul but clearly not very bright.” But he also then goes on to bracket him with Allen Ginsberg as a maker of incantational inventories. The connection resonates: As a red diaper baby, Ginsberg would surely have been exposed to Gold at an impressionable age. Alan Wald, perhaps Gold’s most sympathetic critic and persuasive advocate, has noted Gold’s praise for “Howl” (“the most heartbroken lamentation over the epoch that I ever read”), as well as his admiration for Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and reading the trio next to one another, a kinship between them does emerge.

Chura doesn’t make much of Gold’s affinity for the Beats, which was more literary than political, but he does devote considerable attention to his role in a parallel development that was also influential at mid-century: namely, the folk song revival. No one was more ardent than Gold in opposing the highbrow proletarian music of Hanns Eisler, Marc Blitzstein, and Charles Seeger. Rather, he advanced the notion that Appalachian folk songs and Black spirituals were the authentic songs of working people.

Gold praised Kentucky singer-songwriter and union activist Aunt Molly Jackson as “among the nearest things we’ve had to Joe Hill’s kind of folk balladry.” Later, he championed Woody Guthrie to the extent of becoming his unofficial promoter and exegete. He was also a regular at the Greenwich Village loft where the Almanac Singers, a group featuring Guthrie and Charles Seeger’s son Pete, gathered. “We were famous in the Daily Worker crowd,” the younger Seeger recalled. And he repaid the favor: Comrade to comrade, he comforted Gold with “Guantanamera” as he lay on his deathbed. Seeger’s deep affection for Gold is neither personally nor culturally insignificant. No less than the Beat poets, the folkies were instrumental in the formation of the ’60s counterculture.

Although a doctrinaire communist, Gold also belongs to a dissident American tradition. As Jack Salzman, nearly half a century ago in The Nation, complained: “Just as we continue to resurrect the laundry lists of Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper, so we continue to neglect the important contributions made by such left-wing writers as Mike Gold.” In Michael Gold: The People’s Writer, Chura contests that neglect, reminding us not only of Gold’s life and times but also his legacy. As late as the early 1960s, Gold celebrated a future Nobel laureate with a column in the Communist weekly People’s World, headlined “Bob Dylan—Voice of America’s Youth.” If there were to be a Library of America anthology, I’d put that in too.