ARTHUR DO VAL just wanted to be somebody. A sitting lawmaker in São Paulo’s regional assembly—with, as he boasts in his Twitter bio, the second-largest number of votes of any candidate—Mr do Val rose to fame by heckling lefties at marches. He learned this tactic, he explains, from the documentaries of Michael Moore, an American political film-maker.

Mr do Val has since become a talented and prolific producer of web-friendly content. His team pumps out hundreds of images and video clips weekly through social media. People want to be entertained, he argues, so politics must be entertaining, too. Political arguments should be delivered in funny memes and silly videos which, in Mr do Val’s case, tend to focus on promoting economically liberal ideas and bashing the left.

“I tried being a rock star; I failed. I tried to be a fighter, an athlete; I failed. I was simply a frustrated businessman. Then, I saw in YouTube an opportunity to exploit my indignation,” he explains. “I just wanted to stand out, and by accident, it took me to a political career.”

Mr do Val’s rise from a nobody to a state deputy by the age of 32 was both unlikely and impressive. But he embodies a new transnational class of political entrepreneurs who communicate in memes, videos and slogans. They draw on a global flow of ideas, adapt them to local conditions and return them to the ether. Many are activists or ordinary people. Social media are their most important means of influence—both over their followers and each other. The result is not only a new class of unorthodox politicians, but also the globalisation of political ideas, many from America.

America’s films, television and music are loved everywhere. Its consumer brands are world-beating. Its social-media stars have global influence. As the world’s most powerful country, with huge cultural reach, it has always had a hefty impact on political trends and movements.

In 1990 Joseph Nye, a political scientist at Harvard, introduced the concept of “soft power”, which he defined as “the ability to affect others and obtain preferred outcomes by attraction and persuasion rather than coercion or payment”. Hollywood, pop music, McDonald’s and Levi’s jeans are all expressions of America’s soft power.

For many people beyond its shores, consuming these goods was as close as they could get to sharing the American dream. When the first McDonald’s opened in Mumbai in 1996, Indians queued in their thousands to taste its fabled burger (though made without beef), replicating a scene from Moscow six years earlier. (The opening of a Starbucks in Mumbai a decade ago drew a similar response.) Mumbai’s film industry, the biggest in the world, is called “Bollywood” to mimic its counterpart in Los Angeles. Nigeria has “Nollywood”, Pakistan “Lollywood”.

Even if McDonald’s and Hollywood contribute to growing obesity and unrealistic expectations of police forensics, for policymakers the important thing is that, as Mr Nye puts it, “exerting attraction on others often does allow you to get what you want”. A fondness for American brands is positively correlated with favourable views of the American government. What has changed is that the culture the country exports has expanded to encompass its politics. And in the age of social media, it is memes, not McDonald’s, that are the main vehicle for America’s cultural influence.

Take Brazil. Its political scene is full of YouTubers and Facebook influencers. These include supporters of Jair Bolsonaro, the president; critics of the government such as Felipe Neto, who rose to fame making videos for young people; and a vast market of political content-makers in between. “There is a lot of influence, even unconscious, of the [American] discourse. What’s happening there, comes here,” says Mr do Val, citing debates on face masks or race. This is not as simple as copying and pasting American arguments, he cautions. Rather, America provides the templates that anyone anywhere can apply.

According to Whitney Phillips, a media researcher at Syracuse University in New York, America’s role in shaping political debates comes not just from the norms it promotes. It also “flows from its cultural production—the actual stuff of media and memes”, she writes in “You Are Here”, a new book examining global information flows. One reason America’s influence is greater now, she says, is that “social media is global. And there are way more people outside the United States who use Facebook than in the United States.”

Black Lives Matter sweeps Nigeria

Consider the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests which erupted in America in 2020. They inspired local versions everywhere from South Korea, where there are very few people of African descent, to Nigeria, where there are very few people who are not. In Britain, where the police typically do not carry firearms, one protester held aloft a sign that read, “demilitarise the police”. In Hungary, where Africans make up less than 0.1% of the population, a local council tried to install a work of art in support of the BLM movement, only to earn a rebuke from the prime minister’s office. Last year the Hungarian government released a video declaring, “All lives matter.”

QAnon, a conspiracy theory that holds that paedophile cannibals run America, began circulating some time in 2017. It has since won many adherents outside America. In a small QAnon protest in London last year, people carried signs that read, “Stop protecting paedophiles”. In France it is finding support among gilets jaunes (yellow jacket) protesters. According to one estimate, Germany has the world’s second-largest number of QAnon followers. The conspiracy theory has even spread to Japan, despite the country’s radically different political culture.

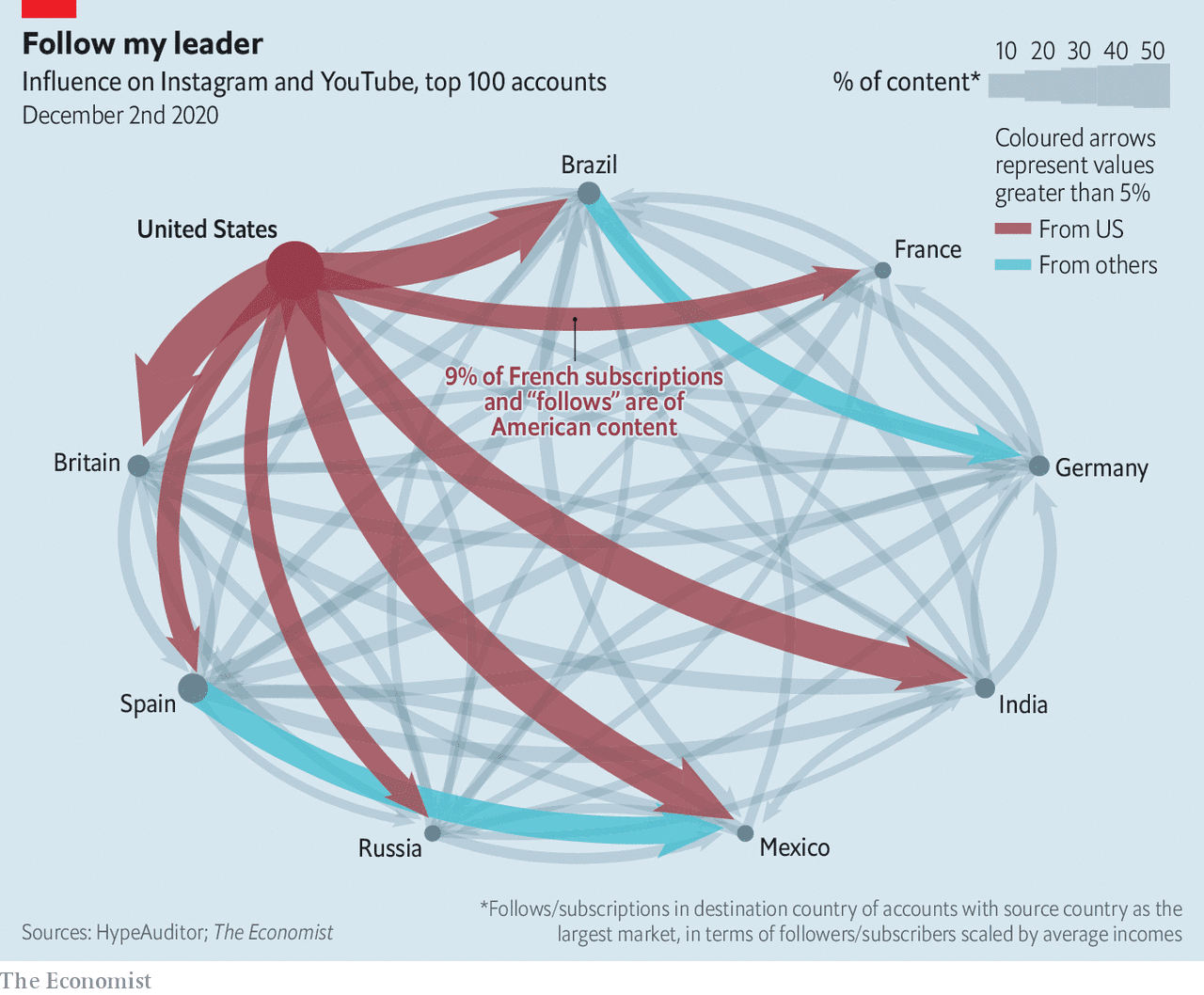

Cultural influence is not a one-way street. British political influencers enjoy big audiences, including in America. The odd Canadian gets a look in. Mr do Val proudly points to the “confused lady” meme as one that started in Brazil but is now in widespread circulation abroad. Yet few people are aware of its Brazilians origins. Nor do Brazilian—or any other—movements inspire similar memes across the world. The ability to influence the world, even if indirectly, is proportional to a country’s cultural heft (see chart).

Much of this is the work of social media. It amplifies new voices, accelerates the rate at which ideas spread, and broadens the scale at which both people and ideas can win influence. But established newspapers and television channels also retain immense influence, even online. CNN is the second-most-visited English-language news website in the world, after the BBC. The New York Times is third. In November Emmanuel Macron, the French president, complained to the newspaper about its coverage of a terrorist attack near Paris. Mr Macron does not contact every media outlet about its coverage. But some 50m people outside America, spread across every country on Earth, read the New York Times online. Of its 5.2m digital subscribers, nearly a fifth are outside America.

Media outlets elsewhere take their cues from their American counterparts. According to analysis by Kings College London (KCL), mentions of “culture wars” in the British press used to be a quadrennial phenomenon, suggesting they cropped up in conjunction with American presidential elections. But in recent years the use of the term has shot up. “We have imported the language of culture wars into the UK wholesale,” says Bobby Duffy, the director of KCL’s Policy Institute.

These factors together help explain why QAnon has gained global name-recognition, lockdown-scepticism has taken on American vocabulary and BLM protests have spread across the world. Just as people everywhere watch Hollywood movies, they also follow American newspapers, television programmes and social media.

The same cannot be said of any other country. Take China. Protests in Hong Kong elicited sympathy and solidarity, but did not inspire similar demonstrations. Few outside China get excited about buying Huawei phones or shopping on Alibaba. TikTok, its only globally successful internet product, is split into a Chinese version—Douyin—and the version used elsewhere. China’s great firewall keeps the rest of the world from getting in, but it also stops Chinese ideas getting out.

Moreover, the openness of America’s politics allows for a ready appropriation of its symbols and iconography, says Craig Hayden, a professor of strategic studies of the Marine Corps University in Virginia. Videos of riots on American streets should, on the surface, damage the country’s standing in the world. Instead people in other countries see unrest in Washington or Minneapolis and think America is “engaged in this kind of struggle that’s parallel to ours”, he says. And America’s aspirational cachet makes its movements all the more powerful. “I can think of a random country somewhere that’s having internal racial strife; we’re not all retweeting what’s going on there,” he adds.

Uncle Sam’s digital megaphone

Just as political power in the age of social media has flowed to disrupters, so too has the power to influence affairs in far-off lands. Social-media users in Minneapolis or Seattle can have an impact on the Instagrammers of São Paulo. Arguments that start on university campuses in New England migrate to the living rooms of old England. The internet promised to help information flow around the world. But social media and their algorithms have just amplified America’s voice. ■

This article appeared in the International section of the print edition under the headline “What’s the Japanese for QAnon?”